Education for All? A Nationwide Audit Study of School Choice

Scope of Data

6,452 charter schools and traditional public schools in 29 states and Washington, D.C. where school choice is enacted

14,806 emailed inquiries observed

Key Findings

Schools subject to choice – both charter and traditional public schools – are less likely to respond to application inquiries from parents signaling their student has a behavior problem, requires intensive special education services, or has a record of poor academic performance.

A field experiment wherein researchers posed as parents emailing inquiries to choice schools revealed application barriers in terms of accessing eligibility and application procedure information.

Other Findings

Both charter schools and traditional public schools were less likely to respond to emails signaling the student had one of the following attributes:

a behavior problem (7 percentage points below the baseline),

a special need (5.2 percentage points below), or

low prior academic achievement (2.4 percentage points below).

Charter schools were less likely than traditional public schools to respond to an email indicating a special need (5.8 percentage points differential).

“No excuses” charter schools, characterized by stricter behavioral policies, were least likely to respond to emails suggesting a special need (10 percentage points below the baseline).

The only charter schools that weren’t significantly less likely to answer emails indicating a special need were located in states that reimburse districts and schools for the realized cost of supporting individual students with special needs.

Findings suggest that charter school applicant pools may be under-representative of students with special needs, indicating that research on lotteries to examine the effects of charter schools should be understood as tied to the set of students who apply.

Methodology & Data Highlights

An audit study with two field experiments across 6,452 charter schools and traditional public schools in 29 states and Washington, D.C. where school choice is enacted

Summary

Educating a student with special needs can cost a school more than ten times what it spends to educate a student without special needs. To address this budgetary burden and ensure access to education for special needs students, federal and state authorities subsidize the cost of required, supplementary support the districts must provide to these students. State and local regulators also create lotteries so that, once students (special needs or not) apply to schools of choice, they are given a random chance at admissions.

Still, schools may impede students from applying in ways that are difficult to detect and cannot be gleaned from existing data. For example, families may find it difficult to understand application requirements or to obtain information about a given school’s quality. All of this could ultimately restrict a school’s applicant pool and distort past findings on charter school effectiveness.

This concern has led many researchers to wonder if high-performing schools perform better because they manage to “weed out” students who are more difficult or costly to educate, even before the application process. In this study, researchers conduct nationwide field experiments and find that schools subject to choice - charter schools and traditional public schools - are less likely to respond to application inquiries regarding students with poor behavior, low achievement, or a significant special need.

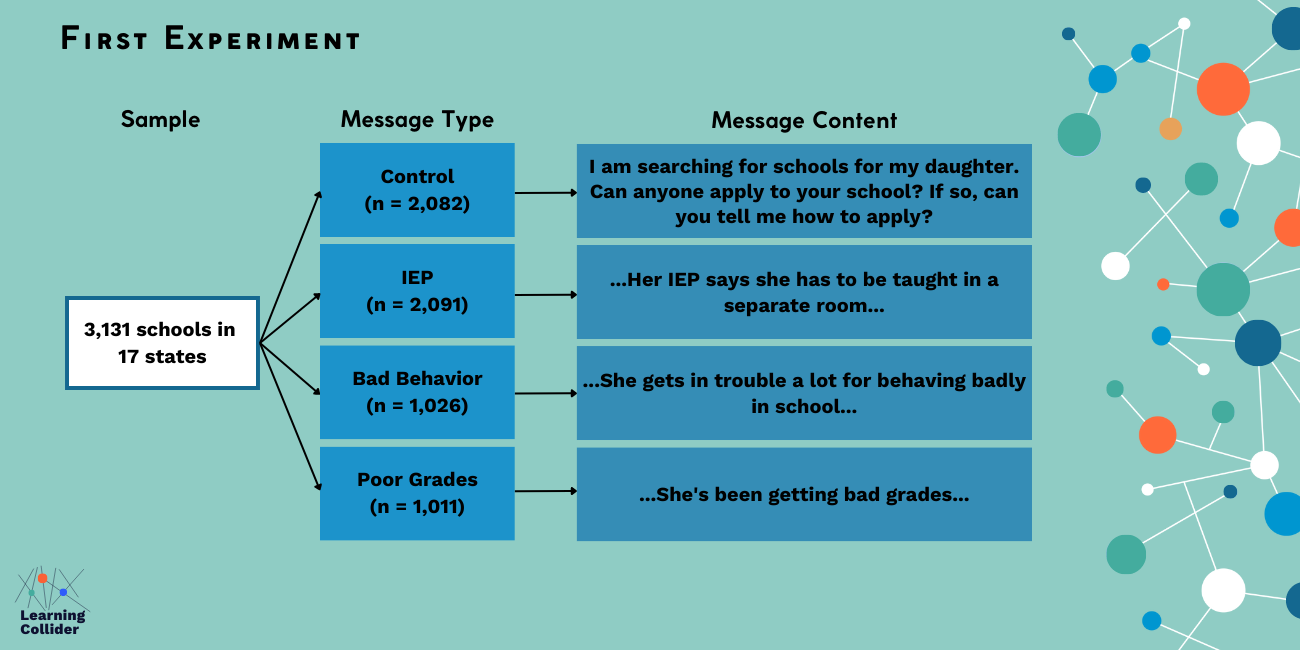

The experiments: emailing nearly 6,500 schools to request admissions information

To understand if schools are creating barriers to application for some families, the researchers built a large audit study involving 6,452 charter and traditional public schools nationwide. This type of field experiment has researchers “enter” the field to create random variation.

Two experiments were conducted:

Researchers emailed only charter schools.

Researchers emailed both charter schools and traditional public schools in order to compare response rates between these two types of schools.

Across both samples, researchers sent emails from fictitious parents to the school asking:

a) whether any student is eligible to apply to the school and

b) how to apply.

Each email mentioned one of the following attributes randomly assigned to the fictitious parent’s student: severe special needs (IEP requires specialized instruction in a separate classroom), behavioral issues, high or low prior academic achievement, or no mention of any of these characteristics (control). The emails also included information - like names - to randomly vary students’ implied gender, race, or household structure.

Emails indicating a student’s behavioral issues or low academic achievement got fewer responses

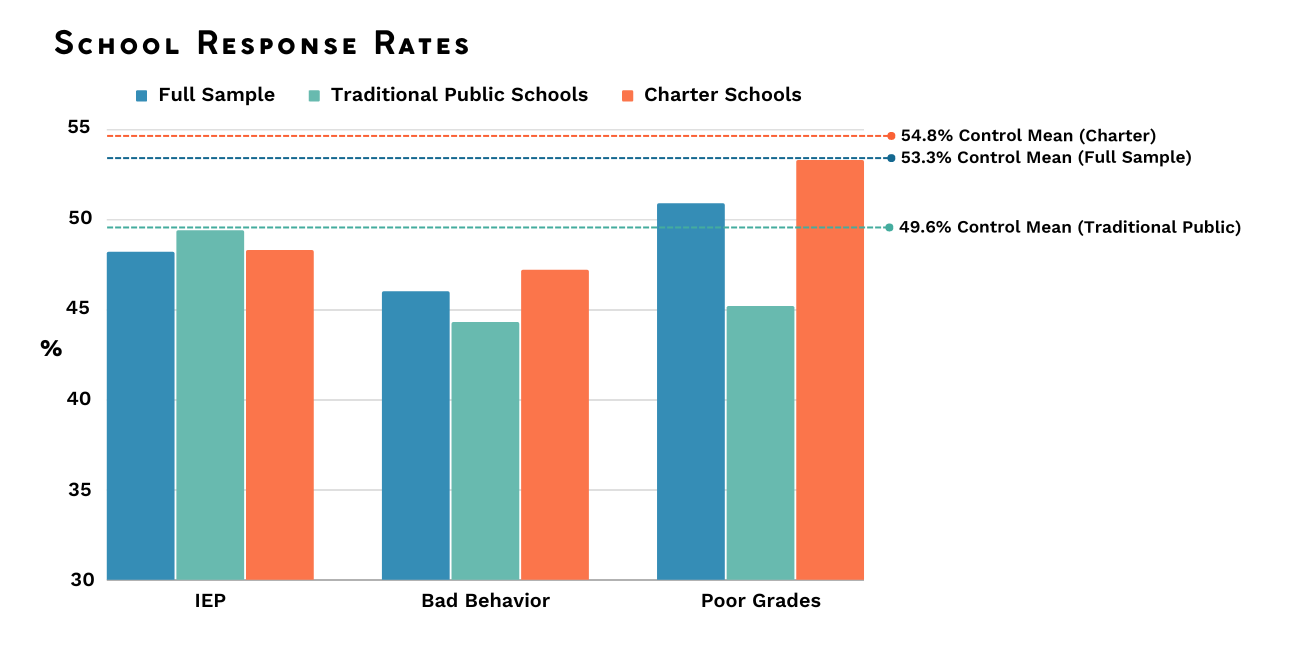

The results were the same across both experiments, showing that both charter schools and traditional public schools are less likely to respond to inquiries from parents of students they perceive as more challenging to educate.

The control response rate across all emails to charter schools and traditional public schools was 53%. Response rates to emails indicating good grades and attendance showed nominal effects on that baseline. This wasn’t the case for emails indicating students had a significant special need, past behavioral issues, or prior low grades:

Emails signaling a behavior problem were 7 percentage points less likely to receive a response.

Emails indicating a student had a significant special need were 5.2 percentage points less likely to receive a response.

Emails signaling a student had low prior achievement were 2.4 percentage points less likely to receive a response.

Overall, schools were 2 percentage points less likely to respond to emails signed by Hispanic-sounding names than to other messages. There was limited, weaker evidence that response rates differed for other groups, including response rates to emails where the name suggested a student was Black.

Evidence shows charter schools create barriers for students with significant special needs–unless states pay most of the cost

For emails signaling a behavior problem or low prior academic achievement, charter schools and traditional public schools responded to parent emails at similar rates. However, for students with severe special needs, response rates were lower at charter schools.

When emails from a parent indicated that their child had a special need, charter schools responded at a rate that was 7 percentage points lower than the baseline. Further, “no excuses” charter schools–often heralded for boosting student achievement–were 10 percentage points less likely than the baseline rate to respond to an email indicating the student had special needs.

Analyzing state-level responses, the only charter schools that didn’t significantly reduce their response rate to emails about students with severe special needs were schools in states that reimbursed districts for a large share of the realized cost of supporting and instructing those students, for example, Wisconsin and Michigan.

It is important to note that some, but not all, charter schools are part of a Local Education Agency (LEA) that aims to ensure students receive interventional support like speech therapy, counseling, transportation, or specific academic resources. If a charter school joins an LEA, it could, in theory, be better positioned to support students with special needs by pooling resources with the LEA. Unfortunately, researchers found that charter schools that were part of an LEA were equally unlikely to respond to an inquiry about a special needs student as those that were not part of an LEA.

Studies on charter schools consider that some students face barriers to applying

The researchers clarify that these findings shouldn’t undermine the internal validity of studies that use lotteries to examine the effects of charter schools. However, the findings do imply that the results of those studies should be understood as tied to the set of students who apply.

The researchers caution that charter school applicant pools may be under-representative of students with special needs or behavioral issues who, though potentially interested in attending the school, face barriers in applying.

*Peter Bergman is the founder and director of Learning Collider.