Randomization Round-Up

Not-So-Random Resources for Social Science Research

By Abbey Vannoy

A quick scan of our lab’s Slack channels would reveal one verb used in high frequency:

Randomize

For those in research, no surprise. Outside the scientific orbit, randomization tends to raise questions (and sometimes eyebrows).

Why — particularly in social science research — randomize?

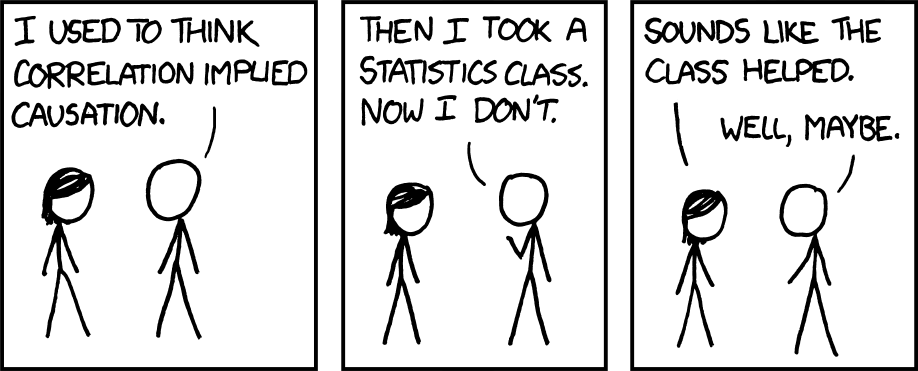

Broadly, randomization is a powerful tool for cutting through the noise and complexity of humans; it’s key to rigorous research and experimentation. Properly randomizing treatment and control groups for an intervention, program, or product can help us generate strong evidence of causality — not just correlation.

Tech teams randomize when A/B testing. Pharmaceutical companies randomize when conducting drug trials. Social scientists randomize in a myriad of settings: education, workforce development, financing, public policy, social safety net interventions…the list goes on.

How effective is high-dosage tutoring at closing reading gaps between student demographic groups? Does a text message (or robocall, email, mailer, etc.) increase vaccination rates? Do cash transfer payments improve economic mobility? Does cognitive behavioral treatment reduce recidivism?

Naturally, randomization in such high-stakes settings can cause unease. It may seem like randomization gives some people the short straw.

The reality is that many existing systems create naturally randomized conditions in high-stakes settings: school lotteries, housing voucher lotteries, case worker assignments, judge/parole office assignments, teacher assignments, and so on. Researchers utilize existing randomizations and design experiments with randomized sample groups.

Moreover, the control of carefully designed experiments is often the status quo - what the population of interest would already experience. The treatment often diverges from the typical, expanding access to something, changing how it is accessed, and/or refining one or more elements of what’s already available.

Whether the conditions are naturally occurring or purposefully designed, the evidence base for what works, what doesn’t, and/or for whom increases with randomization.

Take two (or more) groups that are as close to identical as possible — introducing something new to one treatment group generates evidence to determine if that something mattered.

Evidence can then inform — and broaden access to — more effective programs, policies, and tech products beyond the initial treatment group.

So, to answer the age-old questions of “Does x matter?” or “How effective is y?” or “For whom did z work?”, we need to randomize.

Learn more about randomization — its importance, how it’s used in research, and examples — from some of our favorite resources listed below.

Randomization 101 Resources

J-PAL’s “Why Randomize?” video is an excellent, brief introduction to the benefits of randomization in evaluating impact:

Yale University’s Institution for Social and Policy Studies answers the same question — “Why randomize?” — in simple text format using an example of a Get-Out-the-Vote program. Another great introduction!

For a more detailed — but still accessible for lay readers — explanation on randomization, check out Urban Institute’s page on Experiments.

Our World in Data breaks down the common use of randomized controlled trials in medical studies with data visualizations and comprehensive (but not overly complicated) definitions.

More on Randomization in Tech and Economics

Planet Money’s “How randomized trials and the town of Busia, Kenya changed economics”

Technical Resources

Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA)’s “Using Randomization in Development Economics Research: A Toolkit”

Learning Collider builds, researches, and scales fair technology in Education, Workforce, and Housing. Is your technology platform interested in collaborating on impactful social science research? Connect with us via this form.